35 across

By the end of the drive, Lizzie's ready to sell her car and fly back straight away. The building's dark brick with 80s arches, and already filled with relatives: by the time she and Tara get to their room, she's been stopped three times for conversations she doesn't understand.

"I have no idea who that was," she says after the third, pulling her suitcase along bright bumpy carpet, carrying Tara's apples.

"It was Carol! I know, I hardly recognised her either. I can't believe how much weight she's lost. Wait till you meet her new man friend, too, he's about twenty-five and he's taller than traffic lights. If Terry isn't careful I might steal her diet tips and hunt one another one like him myself."

Lizzie still thinks of Carol as an eight-year-old with headlice, but they're at their room now, so she unlocks the door and pulls her suitcase to the foot of the far bed, over near the window. She lies down. The ceiling is textured with thick plaster curves.

Tara's already swung her bag onto the other bed, and zipped it open. She shakes the fold-lines out of a dress and hangs it up.

"I need something to drink," Lizzie says, but she checks the fridge and it's empty. She never used to mind the tap-water here, but she's not used to it any more, and when she pours a glassfull in the bathroom it's undrinkable.

When she comes back into the bedroom Carol's at the door. "You have a kettle," she's saying. "I'll be dropping in here a lot, then, I can promise you that."

"No tea or coffee yet, though," Tara says. "Or milk."

Carol raises her eyebrows. "No tea, you say," she says, and pulls a tupperware container from her enormous handbag. "I don't have any milk, though," she admits. "But... biscuits." She pulls out another container: individually wrapped mint slices.

"Ohh," Tara says, hands going to her bottom. "I shouldn't, really. I've been so bad this week."

"Come on," Carol says. "Special occasion. You're going to have to get through a lot of cake at the reunion, you know, you might as well get started now. Besides, if you don't grab a couple while Perry's gone then you'll miss your chance. I buy them individually wrapped to slow her down, but she's spooky, she can unwrap them in complete silence and then I turn around and they're gone."

"Still, teenagers," Tara says. "You can't really do anything about it. I wouldn't eat broccoli till I was nineteen."

"No!"

"Ask Mum," Tara says, turning around to bring Lizzie into the conversation.

Lizzie still hasn't taken her boots off, and she doesn't want to listen to this. "I'll go for the milk," she says. "There must be a supermarket around here somewhere."

"It's okay, Mum," Tara says, poking through the sandwich bag. "There's blackcurrant tea, you don't need milk for that."

"Strawberry and vanilla, too," Carol says.

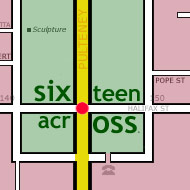

Lizzie would rather have the caffeine. Out on the street she breathes familiar air and feels the street-grid stretch around her. There was a corner shop nearby, twenty or thirty years ago, and she remembers how to turn and walk there; she shuts her eyes and the city around her makes sense for a moment, but then she stumbles into a man in a suit and has to start looking again.

The corner shop's gone, of course, replaced by a whole new building, but she finds a tiny supermarket a little further along, and she laughs for a moment at the racks of iced coffee next to the plain milk.

When she leaves the shop she can't remember which direction she came from. There's no clues: just street lamps that flicker on in puddles, and identical sets of traffic lights. Still, she's bound to find it eventually, regardless of whether she wants to or not. If she misses any exciting news then no doubt Tara will fill her in.

Forty years ago she got through big family events with a sheepish smile at every accusation that she'd grown. It was awkward enough then, but now, on the other side of the line, she doesn't know how to behave. She still remembers deciding, on her twenty-first birthday, that she'd never be the boring conversation-making aunt. She reminds herself of it every time she wants to marvel at tall chubby youths as they tower over her, their hair unmanageably thick, their grins embarrassed. She won't bring up movies or music or school either, and that doesn't leave much.

Surely no other method of assembling a group of people could be so arbitrary. Other school administrators, other people her age, other amateur dahlia growers, other women who use the same shampoo that she does, they'd all have given her a place to start. Other people with her genes, though: no wonder the conversation reduces to how's the baby, how you've grown, your hair looks great. They'll only talk about what they're made of, kidney stones and colds, because what they're made of is the only thing they share. She's always hated compound words, ginormous cyborgs, sporks, but it's all families are. Disparate elements are broken in half and thrown together to create a child. They're all around her, too. Two parents walk by with a small daughter, laughing. The menu she's passing has a "brunch" section, there's a multiplex down the road, and Starbucks must have made it to Adelaide by now so presumably she can get a frappucino as well.

She turns a corner, and she's lost control of the subtleties of right angles now; she's not sure whether she's heading back to the supermarket or away from it, and she doesn't know which would be better anyway. She doesn't really want to find her way back to a daughter who's never lived in Adelaide but who's so much more comfortable here than she is; or to corridors filled with relatives she can't remember; name-tags and fruit tea and, tomorrow, hours in a big church hall crowded with the strangers she grew up with and their strange children.

A bad idea all round, she thinks as she thinks as she turns another corner and recognises the buildings in front of her at last, and they're as hideous and mismatched as all the rest of it. Motoring: yes, fair enough. Hotels, certainly. But both at once? It's no better than smoke and fog, or the fragments of half-people jammed together to make more.