14 across

They spend all night in the forest, which is authentic, and then catch the first bus back into town, which isn't. Annika's looking at the twins' camera, flicking through dozens of pictures and stopping at the ones with her, so Iain ends up next to the man in the wide-brimmed hat and the blue cape.

"It's true," the man says, "that plants grow from the earth, but that doesn't have to mean that the plants are made of earth. It may be earth that holds them together, but since they grow upwards, we can see that they must be part air and fire."

"Yes," Iain says. "Okay." He looks at the window and watches his reflection.

"And see how plants grow sideways, reaching outwards from their core. They can only derive this from water—and there's no reason to doubt that plants have water within them, for it flows out when you crush them in your hand."

It's still dark when they get off the bus to walk down West Terrace, and without his modern-framed glasses Iain can only make out the fading streetlights. He listens instead: birds, occasional cars, loud clanks from the other side of the road that he can't identify. He's lagged to at least a block behind the others, and Annika's dropped back to keep him company, but she's impatient: skipping ahead and turning around to wait, skirts swirling after her on a one-second lag, a blur of red petticoats and a corset worth more than his car. To be fair, his car isn't running these days.

"Look," he says. "I've got work this afternoon. I should have a nap first. I'll leave the keys in the peg tin so you can get in without waking me up, if you want to stay." He's spent half the night standing behind a tree with a sheet over his head, taking his turn at "monster", and he wants to go home.

"Oh, go thou not so soon," Annika says, taking his hand and pulling.

"It's been ten hours."

"Faith, sirrah, thou cans't not know that." She stumbles over the consonsants and tries to spin him around. "It was gone Vespers when we left, and I've heard no call of Matins. Surely thou hast snuck no watch along with thee." He can tell she's been awake too long.

"Okay," he says. "It's been six hours, two hours. I'm tired, anyway." The blurriness doesn't help. He'd assumed that where there's a rule against jeans and buttoned shirts there's a rule against glasses as well; he'd only been in the forest thirty seconds before realising he'd made a mistake, when five of the eighteen players had gleamed moonlight at him from their reflecting lenses. Still, he could have asked about the glasses instead of assuming. He could have taken someone up on the loan of a proper doublet instead of standing around in plain trousers and a dark t-shirt, so maybe he's only got himself to blame for feeling bored and out of place.

"We'll sit down soon and rest our weary feet," Annika says, pulling again, plaintive, and he resists for a moment then follows, trailing behind like her petticoats.

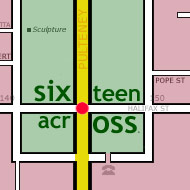

By the time they reach Light Square the others are sprawled on the grass in a circle, unevenly distributed around the circumference to fit into the first bars of sun. They're huge, all of them, their cloaks and enormous skirts even wider on city grass, the golds and purples brighter than they were among trees. The man with the blue cape is lying on his stomach, poking at something; the man with the beard and the spare doublet's sitting against a tree. Annika's skirts puff red around her as she kneels down between them.

"Come along, sirrah," she says, looking up at Iain. He sits down and crosses his legs, and she grins.

"And see," blue-cape man's saying, "when we lift a few small grains of earth, they fall back to the ground. If the world were flat, surely it would fall through space like these grains, being heavy and made of earth; and yet we can see from the constant distance of the stars that it remains in place." On the other side of the circle, the twins are leaning over a game-board. "You can't have 'network'," one of them says. "It can't be more than a couple of hundred years old."

Iain doesn't have a watch, or his phone, so he doesn't know how long he sits there, listening to edges of conversation about why people don't have horns (conclusion: because then they'd have no way to put their weapons aside to make peace) and whether you can spell "wherefore" with only one "e" (conclusion: yes, probably, which is why the invention of Scrabble postdates the invention of stable orthography). After a while the footpaths around the edge of the square begin to fill. He doesn't recognise anyone, but then, he wouldn't, not without his glasses, and sometimes there's a posture or a laugh that seems familiar—maybe that's Colin, maybe that's Isobel. He moves back, into a different patch of sun, further from the others. Maybe passers-by will think he's on his own.

He's almost fallen asleep when Annika gets up and runs over to him. "Wait for me, my love, for all eternity, and also while I go to the toilet," she says, "there's one across the road." After she's gone the man with the beard comes over too: "Hey, we're off to the supermarket for water and something to eat, if you're hungry."

Iain is, a bit, but he wants to talk to Annika. Perhaps if everyone else is at the supermarket he'll get the chance. He stays, and something red stumbles back out of the doorway to the gym and skips toward him, jumping off of the kerb as it starts to cross the road and then sharpening into familiarity. "Sooth," Annika says as she stands above him, blocking out sunlight and looking down, "there was a woman in there who was most startled by my mode of dress."

"I'm sure there was."

She kneels. "But faith, sirrah," she says, taking his hands and pulling him forward, "where be our friends?"

"Over there somewhere," he says, pulling a hand free and gesturing north.

"Your manner of speaking is strange to me my lord, I understand you not." She pokes him in the stomach reprovingly. "Surely they are rather—"

"No," he says, pushing her hand away. He hasn't said "thou" or "whither" since leaving the house, and he's not going to start now. "They're not. They're just over there. In the supermarket. Buying bottled water and chocolate. If you were really being authentic medievalists you'd just drink from the pond, you know. And we'd have gone home when I said we should or I'd have beaten you."

Annika leans back. "Sweetie," she says, "this is Australia. If we were really being authentic medievalists we'd be hunting kangaroos and maybe teasing Dutch mariners. We aren't going for authenticity here."

"Right," he says.

"Oh, come on," she says, laughing. "Wasn't the dragon a bit of a giveaway?"

"I must have missed the dragon."

"You can't have! With the sparklers?"

He hasn't noticed the others getting back. Beard-man drops a plastic bag on the ground and Annika grabs it. "You two okay?" he says.

"Sounds like yellow bile to me," blue-man says. "That's what you get when you eat too many hot dry foods full of earth. Have some ice-cream. Water and air. Also, chocolate." He holds out an unopened Magnum. "I'm supposed to be meeting someone for lunch in an hour or two so I shouldn't really be eating now anyway."

"I'm fine," Iain says. "I think I should just go home and get some sleep. Are you coming?" He looks at Annika. She's frowning, but then he blinks and she's back to normal, tearing open a packet of tim-tams.

"My lord," she says to beard-man, "what splendours thou hast wrought. Surely no human cook has conjured such delights as these. Hast thou been stealing from the very gods?"

Right. "Okay, I'll put the keys in the peg tin. Have fun."

He'll have trouble with the bus numbers on his own, he thinks as he walks out of the square, but he'd rather buses than dragons. Choler and bile fall behind him, and water and fire; every step he takes another element sprouts back into existence, five of them, six, a hundred and six, hydrogen and oxygen running over his fingers as he splashes his hand through the pond on the way past. He can hear someone laughing, back where the grass is made of earth and fire.