20 down

They pick a table outside, under a square umbrella, where Mark stubs out the end of someone else's cigarette and leans back to wait for coffee. Patrick shifts an empty cup and watches criss-crossing twigs on the other side of the canvas, outlined by sunlight.

"You'll be disappointed," Mark says. "They're completely just like muffins, except they're smaller and dearer and they don't taste as good."

Patrick shrugs. "I have to try something I can't buy at home, and as far as I can tell it's a экскурсия в Парк Патриот из Москвы на автобусе, a friand or a vegemite sandwich."

The waitress has just made it to the door, coffees in her hands and cakes on her forearms, when she disappears behind sudden pedestrians, at least a dozen of them plus cameras and children. They separate to flow around the umbrellas, and then reform on the far side. One of the women leans across their table as she passes and drops her cigarette in the ash-tray, murmuring apologies.

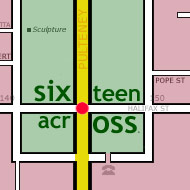

The group stops twenty metres away, turning to cross the road and take photos of a building that's exactly the same as every other building on the street, as far as Patrick can tell.

"They'll be back this way in a minute," Mark says, stubbing out the new cigarette as well.

"How do you know?"

"Historical walking tour. Runs every Thursday."

"Historical walking tour." Patrick scoffs with the authority of someone whose childhood scars were etched by seventeenth-century cobblestones. "Here. I suppose everyone wants to photograph the ancient 1963 office blocks."

Mark slides a column of sugar into his coffee, and taps the paper to shake the last few grains free. "1963's a lot more significant than 1563. What's the point of something that was built hundreds of years ago?"

Patrick hands over his tube of sugar as well, watches Mark tear it open. "Context," he says. "And gargoyles, you don't get enough gargoyles on modern buildings. But mostly context."

"Context that doesn't mean anything," Mark says, waving the hand with the sugar tube and scattering half of it across the table. "Context that depends on people you don't even know. History. History's what you have to make do with when you don't have continuity. See that building over there? That's where my best friend's dad worked when I was six. There used to be a rubbish bin just down the block a bit, and I hit my head on it once. They took it out a few years ago, there, see, where the concrete's a different colour."

"You'll excuse me if I don't put up a plaque." The table next to them's empty, with clusters of plates and the cup they moved earlier: there's another tube of sugar as well. Patrick reaches across and picks it up, to see what happens if he moves it onto their table. Mark bites the top off and adds it to his cup.

"That's the point," Mark says. "I don't need a plaque. If you need a plaque to tell you why something's important, then it just isn't."

Patrick reaches back for another tube of sugar; there's only one left, and it's half empty. He passes it over, and Mark pours it in and stirs his coffee again.

"Is that even dissolving any more?"

"When I first tested how much sugar you can dissolve in one cup of coffee," Mark says, "I was fifteen. My girlfriend was sixteen. We were sitting in the McDonald's on Hindley Street, which is maybe a ten minute walk away in that direction. We put a dozen packets in and it was going to spill over the edge, so I had to drink half of it to make room."

Patrick's trying the friand. "Do I dip this in coffee?"

"No, that's how it's supposed to taste. I did warn you."

"That's where history comes in handy, then. Hundreds of years to establish cakes that actually taste like cake." He forks off another piece; icing sugar clouds from the top, and crumbs fall around the tines.

"You don't need hundreds of years of history for that," Mark says. "You need personal experience. You should know which cakes are good because you've been eating them since you had teeth. When we're born our eyes open onto a thousand local colours, and those are the colours we can see for ever. I've been to the US and England and Wales and Japan and Slovenia and they all looked the same to me, the same trees, the same sky. I'm not trained to tell the differences. I'm only trained to see here. I could walk to every house I've ever lived in from here in an hour and a half, and you think I'm missing out on history?"

"And yet there are tours." Patrick nods at the group rounding the corner down the block.

Mark shrugs. "For tourists. My mum's secretary used to work with the bloke who runs them and apparently he moved away to Sydney for twenty years. He's just trying to catch up now that he's back. It's too late, though. That's what happens when people move. That's the problem with your lot, too, one town for your childhood, one for university, another one to work in, then another one when you move in with someone and then you have to move again so there are playgrounds for the children. Here it's ten hours drive just to get to the next capital. There are six cities in the entire world in our time zone, and this is the only one with more than twenty-five thousand people in it. Half the time when you move house in Adelaide you don't even change bus route."

Patrick scoops up crumbs. The historical walk's headed back at last, on the other side of the road. "Where do you sign up for the tours?"

"I already told you," Mark says, "it won't do any good. The tourist information centre in Rundle Mall, though. My cousin works at the flower stall next door."

"All right," Patrick says. "And your second-year school excursion stopped outside it for lunch once and a friend of yours got lost, and now she's a police officer who arrested your uncle for burglary just down the road."

"Year nine," Mark says. "Not second year. But something like that, yeah. You asked how I knew about the tour, and that's the answer, years and years and years of familiarity. You know how sometimes you'll get people who say they can read each other's minds? Maybe they even believe it, but it turns out they just know each other too well. They can pick up on all the hints that nobody else sees, without even noticing that they're doing it. That's what it's like, it's an extra layer of awareness and memory, it's knowing exactly where you are and where everything else is and recognising someone every time you walk down the street. Without it you're back to just sight and taste and smell and I don't know, the other two. Touch."

"And hearing," Patrick says.

"Mm, that one. It's not really good enough. No wonder you want five-hundred-year-old churches." He swallows the last of his coffee.

Patrick looks around at clouds and windows, tree trunks, dark circles of chewing gum on the footpath. Maybe Mark dropped the gum there, decades ago. Maybe there really are secrets in the graffiti and the salt shakers. "What time does your plane leave?" he asks.

Mark shrugs. "Something impossible. Quarter past seven maybe. I think I'll just stay awake tonight, and sleep on the flight." He sits forward in his chair and rests his head in his hands.

"Sometimes social workers find an old man who hasn't left his house for years," Patrick says. "There'll be piles of newspaper in the spare room, and a thousand empty cans of tuna piled up against the wall. The men don't want to leave, usually, they just want to rearrange the tuna cans."

"Yeah," Mark says. "And then we assume we know better, and try to force them outside, and pretend we're doing good. We don't think that maybe the house is full of details that our eyes are too coarse to pick up on. We don't think about the years the old man's spent watching the sun rise across the same carpet, and learning where the ants get in, and exactly how long it takes the oven to bake a tuna casserole. We don't think about how he can walk through every room in the middle of the night and know exactly where he'll land if he falls over."

Patrick watches him. "Want another coffee?"

"Not really," Mark says, and leans back. "Their hot chocolate is pretty good. Order from the blonde girl if you can, she'll give you an extra marshmallow."