26 across

You can't transform your body and keep the person inside it, not even if you're a god: change into a swan and you're a swan, a bull and you're a bull. You can create где купить экскурсии в Сочи в 2022 году a daffodil in your wake, but you've got to die to do it.

"I imagine you didn't like getting your period either," says Norma, who loved it, and loved pregnancy more, and menopause even more than that.

"That's none of your business," says Perry, still unbleeding at fifteen.

"In any case," Norma says, "you're certainly wrong. Think of Superman."

"Same thing." Perry counts waltz footsteps: one two three, right two three, then stops to glare at two men outside a pub. On the far side she starts again: left two three. "Kent never gets anything from saving the world, he just disappears for a few hours. When he comes back he's still wearing glasses, and there's Lois For Superman graffiti in the toilet with lovehearts all around."

Norma keeps up, just. "I'm sure I wouldn't turn down the ability to fly. I don't think I'd mind too much if I had to do it in disguise."

"And even if the change lasts," Perry goes on, "it doesn't matter. There are already six billion people who aren't you. I don't see why you'd want to get rid of yourself to create another one."

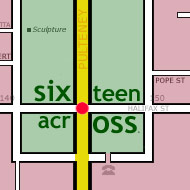

At the end of the street they hit the square and pass trees, fallen leaves and trunks fading slowly back to grey from the streaks of pink and green and yellow where they were soaked with rain. Perry walks over the chessboard inlaid in the grass, and her shoes stop squelching and start to squeak.

Norma sits on a bench and opens her book again.

"You'll get wet," Perry says, hopping from a black square to a white.

"I won't melt." She turns a page, and looks up to see Perry spin around aimlessly on one foot, kicking the other out into the air. She turns another page.

"What're you reading, anyway?"

"You won't like it," she says, holding it out, and Perry steps off the chessboard to look.

"And now their legs," Perry reads out loud, "and breasts, and bodies stood crusted with bark, and hardening into wood."

"I said you won't like it." Norma wriggles her fingers expectantly, and Perry pushes the book into them, grumpy. She steps backward. On the board again, she hops another square forward.

Her hair's fuzzing loose in the damp and the occasional late raindrops. She runs her tongue along the inside of her teeth. "Watch out," Norma says behind her. "You know what happens if you reach the end of the board."

She does; Norma taught her, years ago. She prefers Scrabble, anyway. She hops forward another square, and looks: three more steps to the end.

"It'll cost thousands of dollars," she says, "and I don't even want straight teeth. I don't like smiling. I wish they'd just give me the money and let me buy what I want, or put it in the bank or something. Get the car fixed properly."

"Your mother was very keen on braces," Norma says. "She wanted to be the first in her class. She was very keen on earrings as well, though I suppose not until she was a little bit older. I don't think we let her get her ears done until she was sixteen. It'll save you thousands more than orthodontic costs if you manage to keep off the jewellery."

"Nobody would think it was okay for her to force me to have my ears pierced," Perry says.

Norma watches as her granddaughter hops sideways, one foot to the other, changes of direction that skirt the edge of predictability. The crooked teeth are invisible from here. Ten years from now they'll be straighter and whiter, she thinks, and probably Perry won't use them to bite her fingernails any more, and she'll have dyed her hair away from pale brown. She'll have degrees and suits and shoes with heels, and she'll be happier as well, but now she's turning faster and faster and her sneakers thud into the chessboard as she spins close to the end of the board. Norma looks away, back to her book, not wanting to watch for the inevitable slip.