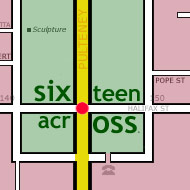

8 across

Arnold stamps his heel, and a lever flips up to hit the drum with a heavy off-centre thod. He reaches behind him to adjust and tries again: thod, thod, thod, thud, and that's better.

On the other side of the road a woman opens her cafe doors, nudging them with a hip as she hoists a sign onto the footpath. She smiles at him for a moment. Once she brought him a sandwich and a slice of cake at lunchtime, to say thank-you for the "beautiful music", but that was a good couple of months ago. He hasn't had much encouragement lately, from her or anyone else, but he has to keep going.

He�s tired автобусные экскурсии по Питеру, and too hot in the suit already, but he tells himself that it's a good sign: as long as it stays warm it�s bound to be a lucrative day. Nobody wants to carry around heavy bags or backpacks in this weather, so they just grab their purses, keeping them close to hand, and that's what he needs. It's not enough to be worth money. He has to be worth time as well, the five or twenty seconds it takes to dig out a coin. Hindley Street is handy for that, lots of women in jeans, lots of men, not so many unwieldy shopping bags.

He flips the bassoon into place and out again, checking the tuning; then the clarinet. The arm squeaks as it swings, and he makes a mental note to oil it tonight. The blonde violinists walk past him, cases in hand, and they�re not the donating sort, but people with instrument cases rarely are; and they smile at him every time, which used to be almost as good as a coin. He likes it when legitimate musicians enjoy him.

For Arnold, legitimate musicians are the ones who get paid by silent electronic transfer, lighter than air; maybe a cheque, at a stretch. Undergraduate string quartets are a step down, with their tiny bundles of rustling notes, handed over by the best man. He can tell that busking is the lowest form of music because the pay is so concrete and so loud: coins clinking underneath the high notes, bouncing out of the open case, rolling down the footpath. There�s so much heft to his takings that he sometimes can�t bear to carry them home. Instead he bundles them up and hides them around the city, ATMs for the bankless: there�s close to a hundred dollars buried in loose dirt in the parklands, another fifty in the cracks of a yellow carpark wall. Sometimes the money goes missing, of course. He slipped an hour�s takings into the plastic of a bus timetable once, and that went, and his stash on top of a university roof disappeared behind a locked iron grid across the top of the ladder. He thinks of the losses as the bank fees he reads about but never experiences first-hand.

It suits the job, anyway: unpredictable, unreliable. Successful busking isn't just about being good. If everyone's dropped fifty cents on the cutely incompetent Suzuki-method five-year-olds, then he'll be out of luck. The competition can work in his favour as well, a few decent players down the road kicking people into the feeling that they should give someone something, but there are never any guarantees.

He starts a waltz as a child walks past, holding onto her mother, and they stop. Parents are usually a decent bet. They're walking slower than other people, so they've got more time to reach for a coin, and they want to encourage their kids to be generous and kind-hearted. The mother pushes some money into her daughter's hand and nudges her forward, but the child shakes its head and buries its face in its mother's trousers, so she has to take the coin back and drop it in herself. Arnold nods in acknowledgement.

The short cellist walks past and smiles as well. They had a conversation once about how Arnold learnt to play, and how many days a week he comes out, and whether he does parties. Later that afternoon he'd taken a break and walked down the alley, and stood under a window, listening to everything inside. Someone had leant out the window to smoke.

"I mean, what does he think he looks like?" the someone had said. "And why doesn't he just go and play somewhere else? Does he think we're going to run out and ask him to take over when someone's sick? Oh no, the conductor's fallen ill, only you can save us now!"

"I dunno," someone else had replied, and he'd tried fitting all the faces he'd seen to the voices, tried to remember what the short cellist sounded like. "Phone the council if it bothers you that much. It can't be legal to busk there, not as much as he does anyway. Plus if the police come he'll run away in a one-man-band suit. You've got to admit it'd be picturesque."

The smoker had seen him when she'd flicked her butt onto the ground, and she'd gasped, pulling her head inside and giggling. He finishes the waltz and rotates the flute-hat to the recorder side, and he wonders how many of the others she's told. He'd been planning to find a new space before long, but he can't, now. He's stuck here, or they'll think he ran away out of shame. He plays as loudly as he can: maybe they will call the police, and give him an excuse to leave. He won't run, he'll just keep playing until they drag him away.