33 across

Max believes in determination, but determination works best against deadlines and opponents and strategies, not against food poisoning. He stops to lean on a wall. The nausea swells and the world diminishes to a buzz; a minute later, or ten minutes, the sounds grow clearer again and he pushes himself back to standing.

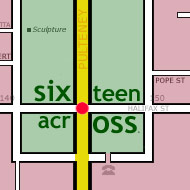

Okay, not determination, then, but maybe perseverance стоимость экскурсии в Петергоф. The air's doing him good, he's sure of that. He could have stayed at the hotel with Dan, but he'd just be lying on the carpet and fighting over whose turn it was to hold the bucket. This is much better, this is the way to do it: he's moving, he's getting his legs to do as they're told, he's working the toxins out. He's almost falling over, and when he ends up against another wall with his eyes shut it's time to admit that perseverance isn't the way either. He stands for long enough to cross the road to the cemetery, where he might scare passing children if he faints but at least he won't be run over.

It's wet and muddy. There's a bench, but he doesn't sit. He'll have to walk back to the hotel soon, lie in a corner somewhere, maybe have a turn with the bucket, and if he sits down he won't want to stand up again. He'll just walk around a bit more, he decides, maybe lean against a tree or two, wait until he's feeling a little better and then start back.

He's only a few blocks from the hotel, and it's confusing how far that seems, now. This must be what it's like to die: the sudden bewildering difficulty of each step, of getting your eyes to focus, of listening to the world without letting it distort into overwhelming white noise. Successive functions switch off until you're left at the centre, and even there your brain's fuzzed and heavy. Max's limbs are slow and difficult to control, but it's more than that. He can't even muster the certainty to decide what he wants them to do, and when he tries he's startled to find himself kneeling on the ground, leaning over, his hands resting in mud, his head dropped against the stone of a grave he hadn't even noticed. But this suit's rented, he thinks, he can't get it dirty. He wonders how that works with the dead, whether you can rent a suit for the open casket and then take it off before you're buried. The buttons, though, imagine trying to undo those with stubbing corpse fingers; he's not dead and even his hands are cold when he pulls them out of the mud, and red where the skin shows under the brown, and he can barely loosen his belt.

Deep breaths again, he can manage those at least. Death must be much worse than this. Even the air must be thick and unmanageable. His hands sink further into the mud, and he pulls free and moves them forward to rest on the clean edge of the gravestone. There's wind, and footsteps, and he hopes nobody's going to notice him. Maybe he's taking up somebody else's grave. He must be, of course, they don't just put the stones down at random and hope that a few of them end up over corpses, but he can't focus on the headstone to read the name, even though it's clean and sharply chiselled. Someone who's only been dead for a little while.

He wonders how long it takes to remember that you've died. It could be years: it must be so much harder to form new memories, when your brain's been called to a halt and the only changes are decay. You must spend months blinking in confusion, and finding even that almost too much, your eyelids damp and uncompliant. Dislodging old memories would be hard too: habit and loneliness propelling you toward the streets to work, to your house, to warm beds and slippers, to buses you've caught two hundred times a year for half your life, that you'd keep on catching for ever if only your legs were strong enough to carry you that far. What is a cemetery, anyway? They're always walled, fenced off, but the walls are too low to keep out anything living. Cats can leap them, small children can clamber over, possums vault in and out and in, ants swarm. It's only the sick and the dead that can't get past.

He wonders what it's like to die after months in hospital. How gradual the change must be; just a slow trailing-off of the visitors who bring you flowers.

It can't last. Thousands of graves filled with confused dizzy people, not understanding why it's so hard to stand, stumbling along pathways with slowly degenerating convictions about what they're supposed to do, welling behind cemetery walls and building up, and up. There are so many of them, each generation stored by the living and then joined by them a few decades later. He pushes himself up into a kneel, for a moment, until nausea overcomes him again and he doubles forward, and even with his misbehaving eyes he sees too many graves to guess at the number. Half of them are hidden under lichen or crabbed branches. What are the dead supposed to do when they manage to walk a few steps, turn a corner or two? They won't be able to remember how to get back to their graves, and the helpful maps and touchscreens are designed for living eyes and fine motor control. Give it long enough and they'll all reach the walls, pushing forward while hundreds more crowd behind them. Eventually, maybe not for centuries but eventually, they'll overflow, flooding onto the footpaths, into the streets and buildings they've been kept from, back to their places among the more obliging bodies of the not-yet-dead. They've done it once before, here, when the cemetery was new and it rained for months and there were floods. You can't build a reservoir without an outlet and expect it to last for ever.

The wind's cold. Max leans over again and coughs, and suddenly his mouth is warm and sour and overflowing, his lunch just missing the stone and pooling on top of mud. It's too viscous to sink in so it flows slowly toward him, and he moves his hands, then shuffles back on his knees, swearing and coughing. He's feeling better. After he coughs a bit more and spits a couple of times, the fuzziness of his limbs starts to clear away. The air thins out.

He's eaten bad food before, and he knows this sudden clarity won't last for ever, even though it feels like it will; and there's the state of his suit, and the orange taste in his mouth, and the muddy handprints on the white gravestone, all reminding him how bad it was just thirty seconds ago. He should get back to the hotel while he still can. He'll be okay for a few blocks, at the very least, and then he'll be somewhere safe when his legs start collapsing again, and his vision blurs, and he can't hear anything except buzzing and silence.