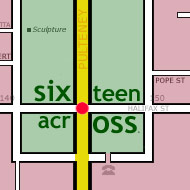

17 across

Pigeons take off behind her as the kettle boils.

"David, how lovely," she says. "I've just made tea."

"I wish you'd keep that fire out during the day," he says. He looks sweet when he's annoyed, all strong and young and petulant.

"You needn't worry, dear, I have a fire blanket," she reminds him. An extinguisher as well, just in case, though she doesn't mention that; the office workers would never have used it anyway.

"Mrs Coningham," he says, sitting down on a milk crate. There's only one chair, and he's always far too polite to use it himself.

"You're a young man, not a child, David, I've told you this before. My name is Violet."

"Violet. They're going to take the scaffolding down next week."

She pegs the teabags on the washing line to dry out. If the scaffolding's going down then she can't afford to be wasteful. She's prepared, though. Another few weeks might have been nice, but they certainly aren't necessary; she has shelter, she has a garden, she has rainwater stored in huge plastic barrels that used to hold cement powder. "That will be fine, dear," she says, and gives him his tea. She should tell him to take his hat off, really, but it makes him look so builderly and competent, with concrete and blue sky behind him, and steam rising from the mug in his cupped hands.

"So you're going to have to leave," he says. "I can tell the foreman you're up here and we'll all help you move your things. We can find you somewhere to go."

"Oh, David, you don't mean that. No, don't make stern faces at me, you know you don't."

He isn't drinking his tea. "You can't stay here."

She looks around. "Of course I can," she says. "It's all self-sustaining. I'll miss your visits, dear, but I have plenty of books to amuse myself with, and this is my home now."

The shed took the longest, one pipe or girder or iron sheet at a time, chosen from the renovation debris at night and carried up stairs and scaffolding. The garden wasn't quick, either, one bucket of dirt from each journey, gradually eroding the flower-beds in the square, but now it's flourishing, cress and zucchini and strawberries and tomatoes and herbs. With the shadecloth it's even safe from the pigeons, which are surprisingly tasty cooked over the fire with basil. She has a six month supply of tinned food, stacked out of sight behind an air duct, to carry her through the lean times. She has four boxes of soap. She's ready.

"I shall be like a god in the desert," she continues. "The views from here, David. You should come up for breakfast at sunrise, before it's too late. I almost left it too late myself. Forty-three years, fifteen of them working just below our feet, and I was certainly in the office by dawn more frequently than I care to remember, but I never once thought to see what the roof was like. I suppose I ought to be grateful that the world is oblivious to the plains that rise above it. I would hardly be able to remain here so comfortably otherwise."

David sighs, and leans forward to put his mug down on the concrete. She does wish he hadn't found her; it torments him so.

"David," she says, trying another tack. "It's a social experiment. I am a pioneer."

"What do you think this is?" he says. "It's not a desert island with a million-dollar prize, it's not a laboratory. It's just a rooftop. And you're a trespasser."

"I comply with the regulations and wear boots and a hard hat during working hours, which is more than I can say for many of your coworkers, and even for you, sometimes, I'm sorry to say." He does have wonderful curls. "Yes, I notice," she tells him. "I see many things from up here. A girl stole a bucket earlier, you know, and then there was that young woman defacing the property with posters. I didn't see you telling them they'd have to leave. Is it my age that concerns you so? It needn't, it simply means that I will die soon, and rest here for ever, among my garden and my pigeons. I am, after all, too old to continue climbing down scaffolding for much longer, so even were it to remain in place my position would be no different." She's lying, just a little; she may be as comfortable without the scaffolding, but there will be a difference. It will make it more difficult for anyone else to climb up. The rooftop will be more readily defensible. A flat top and cliffs on four sides: no military commander could have asked for a better stronghold.

"No," he says, standing up, leaving his cooling mug on the concrete. "I'm sorry, but there could be a fire. You could get sick. It'll be winter soon, and you'll be stuck up here, and what are you going to do when you change your mind? Jump up and down on the edge of the roof and hope someone notices before you fall off?"

"Oh David," she says, standing up as well, "no, please, don't. I have a torch, you know, I could send a morse-code message to the ground if I needed to, I'm quite proficient."

"Nobody would understand it," he says. "People don't know morse code any more."

"I could write you a postcard every week," she says. "To let you know that I'm well. If I buy enough stamps then I'll be able to drop one off the roof every Monday, and someone will pick it up and put it in a postbox. And it's always nice to get mail, don't you think? No, don't leave. You haven't finished your tea. Sit down and look."

From here she can see so many other rooftops, filled with air conditioning ducts, pot plants, old chairs, corrugated iron. They're stepping stones, stretching across the city. When it's dark she feels like she could stride across them if she wanted to, one foot on each, while the cars and trees and people crowd underneath her. Forty-three years moving further and further away from traffic and conversation, up the office block, and now at last she's at the top.

"Look at the flowerbeds," she says, drawing David closer to the edge and nodding down at them: wide circles, half obscured by trees. "And the roads; they're so much prettier from up here, and so much more orderly. Imagine how beautiful this must be at night, and think about how carefully I've prepared, and how little there is to interest me down there nowadays. Would you really make me give up my home?"

She watches him as he squeezes his eyes shut and opens them again. He's a builder, after all, he must understand what it's like to have this sort of view of the world.

"Yeah, okay," he says.

She beams, and takes his hand in both of hers to squeeze it. "I knew you would understand."

"But I'm leaving my mobile phone," he says. "And you have to keep it turned off so the battery doesn't run out, and put it somewhere dry. Wrap it up in a plastic bag in the shed. I'll bring a spare battery tomorrow. And I'll give you my number, so you can phone me when you want to get down and I'll contact building management. Actually, I'll get a permanent texta and write the number on the shed, okay? So you can't lose it."

"My dear," she says. "I should be delighted."

"But you can't just phone me to ask about the weather forecast. You have to conserve the battery."

"Of course, David, just as you say." It's a beautiful golden day and from up here she can tell that it's going to rain, soon. Her tomatoes will be watered. Maybe she'll climb down once the builders have left and go to the library one last time. They won't be able to fine her for overdue books if they can't find her. It's such a relief; she was so frightened she was going to have to push him over the edge.